Story by Arlyssa D. Becenti, Arizona Republic • 2d

More than four years after the closure of an Arizona power plant and the coal mines that supplied it, Hopi tribal leaders are still trying to determine what is adequate compensation for the income they lost.

The Arizona Corporation Commission ordered Arizona Public Service Company to pay the Hopi tribe for the loss of revenue from coal, but the tribe appealed the order because the settlement was based on insufficient evidence and didn’t cover the losses, and in late December the Court of Appeals of Arizona dismissed the case.

In 2021, the commission ordered APS to pay the Hopi tribe $1 million directly and fund electrification projects within the Hopi reservation in an amount “up to $1.25 million” as part of APS’s Coal Community Transition Assistance.

The decision was made after Tucson Power filed a rate application in April 2019, when questions were raised about what would be done to assist communities affected by the transition away from coal-based energy production. In January 2021, APS announced a “Clean Energy Commitment” to end all coal-fired generation by 2031.

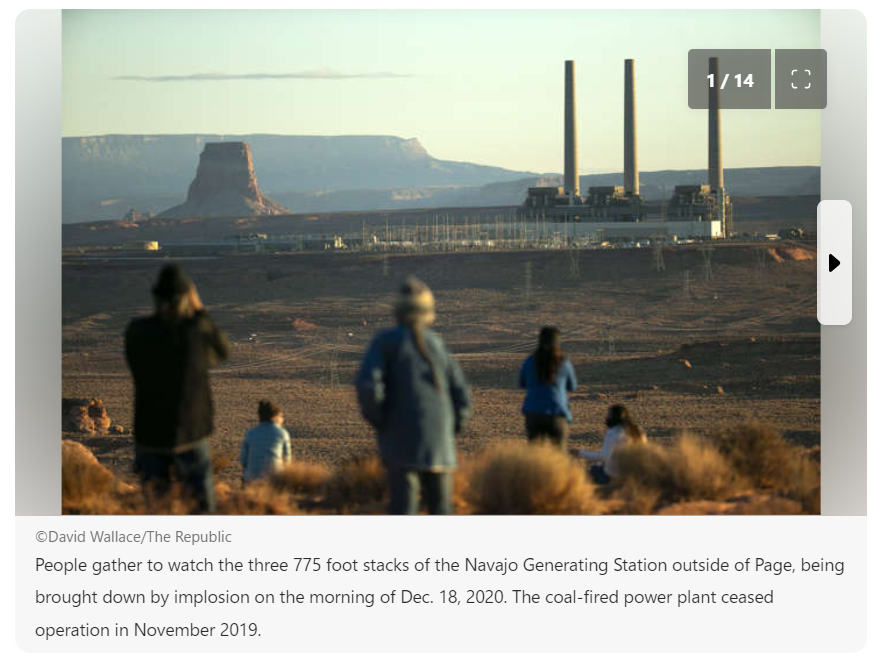

After the APS announcement, the commission considered an administrative law judge recommendation regarding funding within the Hopi reservation and issued the decision on the specific amount to be paid to Hopi. Tucson Electric Power, APS and other entities jointly owned Navajo Generating Station located in the Navajo Nation community of Lechee. The plant closed in November 2019.

In response, the Commission ordered its staff “to open a generic docket involving all Arizona electric utilities to address the impact of the closure of fossil-based electric generation on the tribal communities.”

Hopi officials disputed the amount of the transition assistance, arguing that not only was there not enough substantial evidence used, but the commission didn’t stick to its own rules, discriminated against the Hopi tribe and unfairly denied Hopi a rehearing.

“We do not have jurisdiction to consider any of the challenges to the transition assistance because that portion of the decision was not final,” the court said in its ruling. “We therefore dismiss the Tribe’s appeal.”

During the hearing before the Appeals Court, Hopi attorney Frederick K. Lomayesva told the judges the tribe wanted the court to vacate the portion of the commission’s order of payment to Hopi and to “order the commission to articulate a methodology between how it gathered the facts and how it came to its conclusions.”

He said the issue Hopi has with this case is that there were not enough rational facts gathered by the commission to conclude the amount allocated to Hopi for Coal Community Transition assistance.

“It is very difficult to tell whether or not, other than just looking at the amount, whether it’s discriminatory,” he said. “We feel that it is, but part of that reason is basic failure of the Corporation Commission to articulate some type of reasonable connection between the facts and the conclusion.”

It’s one example of how Hopi and Navajo communities that had relied on coal continue to work toward receiving transition assistance after the closure of the Navajo Generating Station and Kayenta Mine.

Navajo Generating Station began operating in 1974, and was the largest coal-fired power plant in the western United States until it closed in 2019. It received a majority of its coal from Peabody Energy’s Kayenta Coal Mine. Kayenta Mine, located on Nation land, and received some of its coal from a “joint use area” shared with Hopi.

Economic help: Navajo residents seek ‘just and equitable’ help after closure of power plant, coal mine

Power plant’s closure hit Hopi budget

Although communities say coal brought no benefit to the land, people’s health or animals, the coal industry contributed significantly to both Navajo and Hopi general budgets. Both tribes were significantly impacted by the closures of the mines and the power plant due to the loss of jobs and the decrease in revenue that no longer flowed into tribal coffers.

“When any community relies on its long term, ongoing relationship with power, it puts itself in a detrimental position,” Lomayesva told the judges. “The unilateral cost of closure is not simply the cost of the company, or the rate payers, there’s other externalized cost that are involved and that’s exactly what happened here.”

He said the Hopi tribal government is the major employer for its people and for most of the income to be taken away as it was with the mine’s closure, there would be consequences. Since the closure of the power plant and Kayenta coal mine in 2019, Tribes have lost up to 80% of their annual revenues and 1,500 jobs.

“When you have a majority of the income to a particular community in Arizona that can no longer rely on that income, it causes devastating effects,” he said. “Which we are still undergoing at the Tribe.”

In 2019, Hopi began the task of setting a new budget without the revenue it would receive from the Peabody closure and trying to brainstorm how to make up for it.

In 2016, Hopi had a budget of $21 million, according to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. Fast forward to December 2023, when the Hopi Tutuveni newspaper reported that the Hopi Tribal Council adopted and approved its general fund budget of $17.4 million for the 2024 Fiscal Year, a 17% decrease from the pre-coal mine era.

The U.S. Department of Energy and eight federal agencies announced two agreements with the Hopi Tribe in December and an amended agreement with the Navajo Nation supporting the tribes’ economic revitalization efforts.

The multiyear agreements aim to ease tribal access to federal funding available through national policies, including the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors and Science Act, the Inflation Reduction Act, and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, along with programs offered annually by agencies, according to DOE.

“Our intent was to amass available federal resources and make sure tribes are aware they exist and can access them,” said Tommy Jones, a deployment specialist with the Office of Indian Energy. “Tribal-led nonprofits and non-governmental organizations will play a pivotal role, partnering closely with the tribes to secure funding and implement the projects. These organizations have the capacity and motivation to conduct projects.”

Study results: Pollution from coal-fired power plants led to hundreds of deaths in Arizona, NM

Federal funding barriers remain

That announcement came a couple of months after Hopi Chairman Timothy Nuvangyaoma testified during a Senate Indian Affairs Committee roundtable discussion, “Implementing the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act in Native Communities,” where he explained how difficult it is to apply for federal funding.

About 85% of homes are currently without electricity on the Hopi reservation, Nuvangyaoma said, and the coal-impacted rural community is disadvantaged to a large degree.

“We’ve had our own challenges in the form of proposals that we’ve been able to submit,” he said. “Cost matches are a big hurdle we are dealing with right now. Some of the funding we are looking at to get a solid electrification for the Hopi Tribe is difficult.”

Navajo Generating Station’s main purpose was to provide electricity to Phoenix, Tucson and Las Vegas, cities hundreds of miles away from the former power plant and coal mines, but in the backyard of Hopi and Navajo communities, where to this day a majority of residents continue to live without electricity.

The Build Back Better Regional Challenge, a program under the Department of Economic Development’s American Rescue Plan, is aimed at enhancing economic recovery from the pandemic and revitalizing American communities, particularly those that have faced decades of disinvestment. Hopi applied for this program and was awarded $500,000 for Phase I, which involves developing a plan and project.

“We have a great plan in place,” said Nuvangyaoma. “Unfortunately, we weren’t selected. It still bothers me because we have a 500 kV line running right across our reservation. So we downscaled the project and the cost match was decreased from 50 to 20%.”

He noted that even with the reduction of cost match it would still cost the tribe $10 million of the reduced tribal general budget. In 2023, the budget was at $17 million and the year before that it was at $16 million.

“NGS was abruptly shut down which the government has a hand in ownership. When we are talking about a cost match we are talking about roughly 65 percent of our general fund budget,” said Nuvangyaoma. “If we want to create a stable electrification we are challenged with making hard decisions. Do we shut down elderly services? Do we shut down the schools? It’s a non-starter. There are these barriers that are still in place.”

The Hopi Tribal Council and attorney Frederick K. Lomayesva did not respond to requests for comment.

Arlyssa Becenti covers Indigenous affairs for The Arizona Republic and azcentral. Send ideas and tips to arlyssa.becenti@arizonarepublic.com.

Source: Hopi tribal officials continue to pursue compensation for loss of coal mine revenue (msn.com)